The man in stripes

Published 5:06 pm Wednesday, December 2, 2020

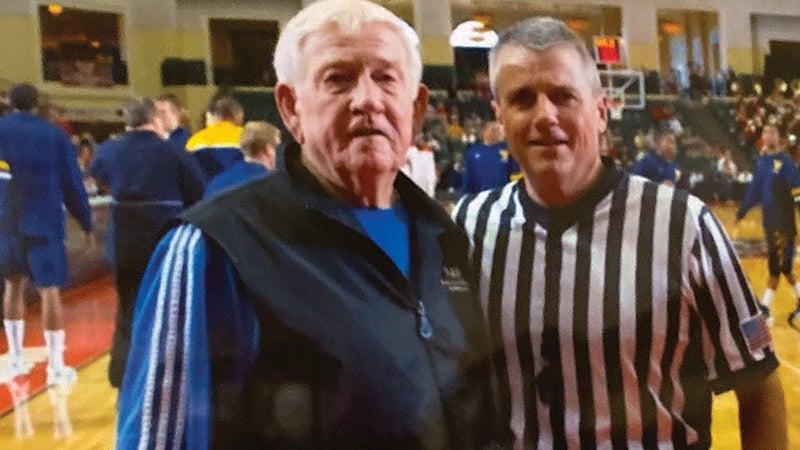

- Bryan Kersey was inspired by his father, Jess Kersey, an NBA referee.

Story by Phyllis Speidell

Photos by John H. Sheally II

Basketball fans watching a game generally focus on the ball, the players and the coaches rather than the referees.

That, Bryan Kersey says, is the way it should be. Kersey, a Carrollton resident, was regarded as one of the best referees during his 30 years as a Division I basketball official. In March 2016, he moved up to supervisor of men’s basketball officials for the Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC).

The referees, Kersey said, are there to facilitate the game and to assure it plays out fairly, by the rules, while they remain low profile.

“We already have ugly shirts on,” he joked. “We don’t want to stand out any more.”

Regardless of its fashion score, that black-and-white-striped shirt is a badge of honor for Kersey and the other referees who spend years running the court with men half their age, assuring that fouls are called equitably and bounds are kept. For Kersey, the referee’s shirt is also a legacy. His father Jesse “Jess” Kersey refereed in the NBA and ABA for 37 years — and inspired his son to join the officiating ranks.

Bryan Kersey started as a ball boy at the Hampton Coliseum when the Virginia Squires played and was in 10th grade when he reffed his first game for a middle school. His Division I officiating career included the Big South Conference, the Colonial Athletic Association and the Atlantic 10 before he joined the ACC officials in 1990.

Kersey said he would have refereed every night in the ACC if he could have — not too surprising considering that sports, particularly basketball, run strong in the Kersey genes. In addition to his father’s officiating career, Kersey’s brother, Todd Kersey, is the chief operations officer of the Virginia Athletics Foundation. His nephew, Grant Kersey, a 2020 University of Virginia grad and the four-year team manager for the UVA men’s basketball team, also played in 11 games. Shooting 5-for-5 from the foul line and 5-for-5 from the field, he was a fan favorite.

The referee’s shirt Bryan Kersey wore officiating at the 2015 Final Four hangs, framed in a shadow box, in his office at the Kersey, Sealey, Clark and Associates insurance brokerage in Newport News. A half-dozen signed basketballs, enshrined in clear acrylic cases, and a wall of TV screens indicate how seriously Kersey takes the game. Asked if the rumor is true that he took on the insurance business to have a flexible schedule, enabling him to officiate, Kersey answered in one word — “Absolutely!”

The office TVs are essential to his job of overseeing the ACC’s officiating. During a normal college basketball season, Kersey is in his office every Saturday from 11 a.m. to 11 p.m. watching games on half a dozen screens. Eyes trained on the referees, he watches every call and how it’s made. With so many games televised, he said, “You have to be conscious of bad optics — TV can make you or break you.”

“Over the years I learned from the refs I worked for,” he said. “Now that I am the boss, I am teaching every day.”

Refereeing requires respect.

“Respect is a two-way street,” Kersey said. “My new guys in the ACC have to earn that respect. Going into a game, we know there are some coaches we will have to talk with more than others. If coaches get upset — you give them their time and let their personalities show. That way a mutual respect grows over time. “

Coaches know how far to go, he said, but some players, especially freshman, will test the referees.

“If a player is giving us a problem, we talk and bring him off the ledge,” he said.

Referees rarely disagree on a call he said, but it’s most likely to happen when one calls a block and the other calls a charge.

“We call that a “blarge,” Kersey joked, “But we get together, talk it over and make a decision.”

Referees’ minds are trained to make on-the-spot decisions, but has the instant replay affected that decision making?

“Instant replay allows us to get the plays right — and sometimes right a wrong,” Kersey said. “It showed us that we have to be better at clock management and that you have to ref off the ball. College players are so good they know where the officials are and can throw an elbow any time they want, knowing if they are out of our sightline.”

“With experience and familiarity, coaches believe you,” Kersey said. “But when fans know your name, they call out to you when they’re unhappy with a decision. I always knew my last name was Kersey, but I’ve heard all sorts of first names — ‘I hate you’ ‘Your Mama hates you,’ and others I won’t mention.”

Refereeing shaped his life. Married for 36 years, he calculates he spent 18 of those years refereeing, often gone for 30 days at a time.

“A few games a year grew to 70 to 100 nights a year,” he said.

His wife and children came to Orlando, Fla., for Thanksgiving every year because he officiated a tournament there. To stay in shape to run the court, he ran three to four miles a day, did street sprints from mailbox to mailbox, and followed cardio training videos.

“On the good side,” he said, “the career has taken me to Alaska and St. Thomas. I was the son of a somebody and I was a rock star in the eyes of my kids and their friends who saw me on TV.”

“When the police escort you into the venue and you step on that court, you know you are where you need to be, and then the adrenalin kicks in and you focus solely on what you are doing,” Kersey said. “Even working AT&T Stadium with a crowd of 80,000-plus, it’s still a 94-by-50-foot basketball court.”

Apart from being extreme perfectionists, referees are normal, sports-loving people, he said, adding, “We all care about what we do and we don’t care which team wins — officiating is the greatest life we could possibly want.”