Behind the walls of Bacon’s Castle

Published 3:55 pm Tuesday, December 7, 2021

Panel discusses symbolism behind ritual concealment

When Preservation Virginia, the privately-funded statewide organization that now owns Bacon’s Castle, began restoring the 17th-century Surry County homestead in the 1980s, its historians discovered a circa-1675 coin beneath a floor tile in the home’s basement.

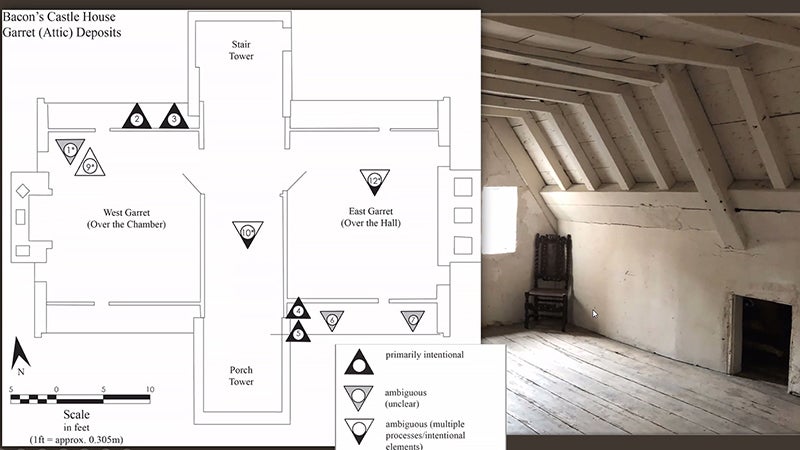

Upstairs, inside the knee wall of the home’s attic, they’d found shoes believed to date from the 1820s to 1840s, bottle fragments, a shard of window glass with the name “W. W. Rowell” etched into it, and a number of other artifacts from the past 350-plus years.

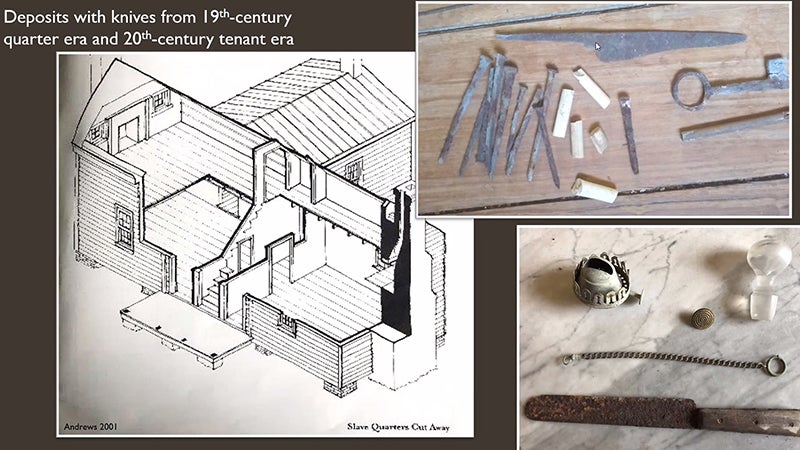

In a detached 19th-century outbuilding — constructed as housing for enslaved Africans, then repurposed after the Civil War for use by sharecroppers — a knife with its handle missing, loose iron nails, a key and fragments of white tobacco pipes had been concealed behind a loose brick in its fireplace at some point during the structure’s history.

But how these items came to be concealed within the plantation’s walls, if indeed all of them were intentionally hidden, remains a mystery — one Rebekah Planto, a graduate student at the College of William & Mary, is now exploring in her doctoral archeology thesis on ritual concealments.

During the home’s initial restoration, Preservation Virginia had documented each find by marking on paper exactly where each artifact had been discovered. But the artifacts themselves ended up spending the next 30 years in storage boxes labeled “architectural finds.”

“Much of it has not yet been extensively researched, which makes it a fantastic resource for grad students like me,” Planto said.

Among her goals is to answer, or at least hypothesize, which items were hidden intentionally as opposed to having become part of rat nests or fallen through cracks when the historic home’s inhabitants were sweeping or using the hearth.

The “clearest evidence” of ritual concealment is the heel of a man’s shoe, which appears to have been deliberately and cleanly cut in half and “hidden carefully” in an area of the attic that had been accessible and opened from time to time, Planto said.

The key and other items found behind the loose brick in the outbuilding were also likely concealed intentionally, since someone would have needed to take the brick out, hidden the items, then put the brick back.

“This is not … a rat’s nest or things falling through a hole in the floor,” Planto said.

A key, she added, “could be a practical thing to hide.”

But as to whether the concealment was ritualistic, the loose nails found in the attic and behind the brick in the fireplace are the “wild card,” she said. “An iron nail, in some cases, could be a pointed iron charm, and in many, many cases … an iron nail is an iron nail.”

In the case of the nails concealed behind the fireplace brick, “I think the nails probably are symbolic in some way,” Planto said.

Planto participated in an online expert panel discussion on Dec. 1 titled “Behind the Walls at Bacon’s Castle: Found Objects and Ritual Concealments,” during which she and other archeologists and historians weighed in on the potential symbolism of the finds.

Jessica Costello of the National Park Service’s Northeast Museum Center, researched concealed footwear for her master’s thesis after taking an interest when her mother found a child-sized, buttoned boot between the walls of the family’s childhood home in upstate New York.

The act of concealing shoes is “not well documented” and “theories behind the meaning of the ritual are just that — theories,” Costello said.

According to Costello, the act of concealing shoes may have been intended to deter witches or evil spirits, assure good economic fortune, prevent bad luck or symbolize grieving.

“Discoveries near openings like chimneys, doorways and windows support the hypothesis of a protective charm,” Costello said.

In gravestone iconography, however, an empty shoe typically symbolizes the death of a child, Costello explained, so concealing a child’s shoe may be a grieving gesture for a child who died.

“Concealed shoes are often well-worn,” Costello added, making the well-worn pair of women’s or adolescent shoes found in the attic at Bacon’s Castle consistent with finds in other historic homes.

Sara Rivers-Cofield of the Maryland Archeological Curation Lab, whose expertise includes small finds and metal artifacts, then spoke on the potential symbolism of the loose nails and circa-1675 coin.

“Iron, especially if it’s pointy or sharp, is considered to be protective,” Cofield said.

Coin magic, she added, goes back thousands of years to when ancient Greeks would conceal coins in their ships for luck. The belief and practice later evolved into a ritual for protecting dairies and other perishables from witches or curses.

“You could do that either by placing the coins at the corners of buildings or keeping a coin on hand to throw at the butter churn if the cream won’t turn into butter and you believe a witch is causing that,” Cofield said.

“Pretty much as soon as you get slavery in the U.S. … the coin magic very quickly spreads into the African American community,” she added, referencing a 2004 publication by James M. Davidson.

According to that publication, there was a belief among enslaved Africans that African-style conjuring didn’t work against white people, and so they adopted European-style charms to use as protection from their oppressors.

“They’re a way to turn an everyday item into a combat against the feeling of helplessness … and so it makes a lot of sense that you’d get a lot of this adoption of these beliefs,” Cofield said.

Brenna Gheraghty, an archeologist at Bacon’s Castle, then spoke on the symbolic use of concealed bottles — specifically her discovery of a “witch bottle” during her time as curator of Chippokes Plantation State Park, which is also in Surry County.

Witch bottles, she explained, are a form of folk magic of European origin. They consist of a bottle or other vessel filled with materials intended to counter a bewitchment or be placed preemptively in the structure of a house on the belief that it would ward off illness, particularly urinary tract infections or kidney disease.

“The urinary system illnesses were often considered to be caused by a witch, so in this case, the witch bottle was a way to deflect the illness back onto the witch who had caused that,” Gheraghty said.

In 17th-century Europe, these were typically stoneware bottles, but when the tradition migrated with Europeans to America, American witch bottles tended to be almost exclusively glass. The afflicted individual would fill the bottle with his or her urine, then add pins or nails, Gheraghty explained.

“Pins or nails are most commonly what help us identify witch bottles … they are believed to symbolize the pain of the individual who made the charm,” Gheraghty said.

The idea was then to bury the bottle in the ground, typically upside down. As of 2014, a witch bottle containing 25 pins and three iron nails buried upside down near a doorway in the Great Neck area of Virginia Beach had been the only such example of this ritual discovered in the state, but Gheraghty found another in 2018 at Walnut Valley, home to the oldest standing slave quarters in Virginia.

The property, which dates to 1816, is now part of the Chippokes Plantation State Park. Gheraghty discovered the bottle under a section of bricks from the hearth that had been removed during structural repairs.

What’s unusual about the Chippokes witch bottle is that it was found buried right side up and “found in an enslaved African context,” Gheraghty said.

According to Jennifer Hurst-Wender, director of museum operations and education for Preservation Virginia, Bacon’s Castle is planning a summer 2022 exhibit of some of the artifacts found within the home’s walls and floors.