Cold case closed? Police say DNA links Lancaster man to 1987 IW double murder

Published 8:21 pm Monday, January 8, 2024

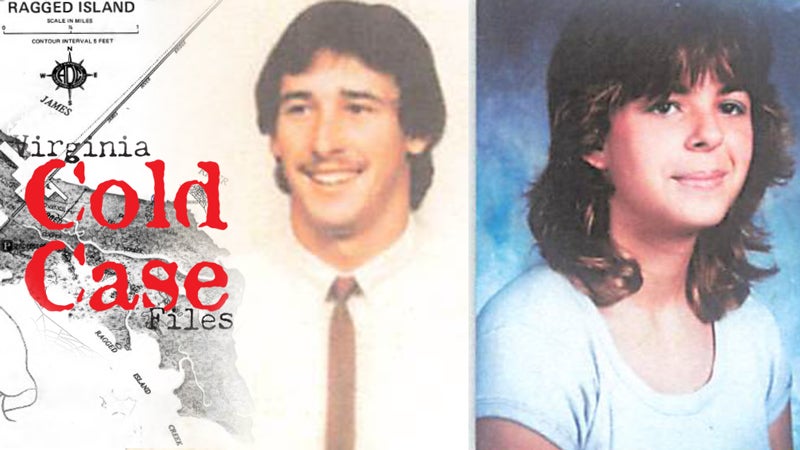

- David Knobling, left, and Robin Edwards were found shot to death on Ragged Island's shoreline in 1987. Virginia State Police say new DNA evidence has identified the killer 36 years later. (Photos courtesy of Virginia State Police)

Virginia State Police say DNA evidence points to a deceased Lancaster County man – Alan Wade Wilmer Sr. – as the likely killer in a decades-old Isle of Wight County double murder.

On Sept. 21, 1987, an Isle of Wight sheriff’s deputy on nighttime patrol found 20-year-old David Knobling’s Ford Ranger pickup truck abandoned at the Ragged Island wildlife refuge – doors closed but unlocked, driver’s side window down and its radio left playing with no one inside.

Two days later, a beachcomber found the bodies of Knobling and 14-year-old Robin Edwards on Ragged Island’s shoreline roughly a mile from the James River Bridge. Both had been shot in the back of the head at close range.

The case stayed cold for 36 years. According to State Police spokeswoman Corrine Geller, Wilmer had been one of several suspects investigators had considered over the decades, and upon learning of Wilmer’s 2017 death, were able to posthumously obtain a genetic sample to compare to DNA preserved from the crime scene.

Last summer, “the Virginia Department of Forensic Science issued a certificate of analysis confirming a genetic match to Alan Wilmer Sr.,” Geller said at a Jan. 8 press conference held at the State Police’s regional headquarters in Suffolk.

The sample obtained from Wilmer’s body also proved a match to DNA belonging to the killer of 29-year-old Teresa “Terri” Spaw Howell, who was found raped and murdered in 1989 in the city of Hampton. According to Hampton Police Capt. Rebecca Warren, Howell was last seen alive on July 1 of that year – a Saturday – at 2:30 a.m. at the former Zodiac Club, which had been a popular nightspot off Mercury Boulevard. Roughly eight hours later, construction workers found female clothing at the edge of the woods off Butler Farm Road and eventually came upon an unidentified woman’s remains. Police identified the remains as Howell’s and determined the cause of death to be strangulation after her family filed a missing-person report in York County three days later.

Articles of Robin’s clothing had also been left near the Ragged Island crime scene in Knobling’s truck. Robin’s older sister, Janette Edwards Santiago, had recounted other similarities in a 2022 interview with The Smithfield Times ahead of the then-unsolved crime’s 35th anniversary.

The then 19-year-old Santiago had been living on her own when she received a phone call from her parents on Sept. 19, 1987 – another Saturday – asking whether she’d seen Robin that evening. She answered, “no.”

“I didn’t think a whole lot of it at the time because she had run away a couple months previously and was gone for two weeks,” Santiago said, noting Robin hadn’t been on speaking terms with her since she’d told on her sister for having ridden her bicycle from their parents House in Newport News all the way to the Coleman Memorial Bridge in York County.

As Santiago recalled from her mother’s account, Robin had arranged a date with Knobling’s cousin Jason, on Sept. 19, which would become the last time anyone saw David or Robin alive.

Jason, David and David’s brother, Michael, had shown up at the Edwards home in David’s Ford Ranger to take Robin to a movie that ended up being sold out. The four went to an arcade instead, dropping Robin back at her parents’ house around 10 p.m. Once home, Robin put her younger sister, Pam, to bed, but went back out later that night with David.

Why the two ended up traveling all the way across the James River Bridge to Ragged Island, and whether they did so willingly, remains a mystery. Police didn’t elaborate at the press conference on whether or how Wilmer knew his victims.

“For 36 years, our families have lived in a vacuum of the unknown,” representatives from the Knobling and Edwards families said in a joint statement. “We have lived with the fear of worrying that a person capable of deliberately killing Robin and David could attack and claim another victim. Now we have a sense of relief and justice knowing that he can no longer victimize another.”

“We’re not saying these cases are closed; they’re resolved for right now, because we know there’s a lot more work to do,” Geller said.

The next task, she said, is to try and piece together a timeline of Wilmer’s life to identify if there were any other victims.

Who was Alan Wilmer?

Wilmer, 63 at the time of his 2017 death in Lancaster, was 32 and working as a commercial fisherman at the time of the Ragged Island murders. He owned and frequently lived aboard a 1976 fishing boat named the “Denni Wade,” which he would dock at marinas in Gloucester and Middlesex counties and throughout Hampton Roads. He was known to drive several trucks, including a distinctive 1966 blue Dodge Fargo pickup with the custom license plate “EM-RAW” – a possible reference to his farming mainly clams and oysters.

According to Geller, Wilmer was also known by the nickname “Pokey.” He also ran a tree service and was an avid hunter.

Geller declined to elaborate on how and when police began to suspect Wilmer of either crime.

“Part of the cold-case philosophy is to go back over, to start relooking and going back through all the witness statements, all the evidence, and it’s a very time-consuming, very complex but very effective way,” Geller said.

Because Wilmer’s criminal record didn’t include any felonies, police didn’t have his DNA on file and weren’t able to obtain a sample to test until after learning of his 2017 death. Wilmer, Geller said, was one of several suspects whose recently obtained DNA was submitted for analysis.

Wilmer’s family, in a written statement distributed at the press conference, said news of the DNA match came as a “complete and horrific shock.”

“The man who committed these crimes was not someone we knew,” the family’s statement reads. “The revelation of what he’s done has deeply impacted our family as we are forced to reconcile who we believed him to be with the unimaginable things he has done. We deeply mourn the victim’s families and the community and have them in our prayers. We can’t imagine what they’ve gone through for all these years.”

“Let us know if you knew (Wilmer), how you knew him, what encounters you had so we can build that timeline and find out if in fact there are other victims out there,” Geller urged the public.

Former Isle of Wight County Sheriff Charlie Phelps, who inherited the Ragged Island case upon his taking office in January 1988, told the Times in 2022 that he long suspected a different man – Samuel “Sammy” Rieder – whom the new DNA evidence appears to clear of the crime.

A few months into his first term as sheriff, Phelps had been investigating the reported theft of several firearms from an Isle of Wight woman’s home and came to suspect the woman’s son. The son, Phelps told the Times, ended up confessing to taking a gun from his mother’s home and selling it at a pawn shop in Mississippi, but then began talking about a roommate – Rieder – who’d lived with him and his mother in Isle of Wight.

According to Blaine Pardoe’s and Victoria Hester’s 2017 book, “A Special Kind of Evil: The Colonial Parkway Serial Killings,” then-28-year-old Rieder had called in one of the original tips the Sheriff’s Office had received when investigating David’s and Robin’s initial disappearance.

As Phelps recalled, Rieder initially claimed to have stopped at Ragged Island out of curiosity on Sept. 23, 1987, when David’s and Robin’s bodies were found, then later claimed to have seen Knobling’s truck parked at Ragged Island days earlier.

Rieder’s final version of events, Phelps recalled, was that he had taken money out of Knobling’s wallet, which had been left in the truck, but denied having anything to do with David’s or Robin’s deaths. The Times, as part of its 2022 reporting on the then-unsolved Ragged Island case, obtained a copy of Rieder’s death certificate, which states he was found dead in his Chesapeake mobile home the morning of Aug. 8, 1990, hanging from a doorknob with an electrical cord around his neck. He was 31 at the time of his death.

One ‘Colonial Parkway Murder’ solved?

The FBI’s Norfolk division has for years linked the Ragged Island cold case to three other unsolved double homicides with similarities from the 1980s known as the Colonial Parkway Murders.

The first occurred in 1986. On Oct. 12 of that year, U.S. Park Service rangers found the bodies of 27-year-old Cathleen Thomas and 21-year-old Rebecca Dowski inside Thomas’ car in a wooded area near the York River off the Colonial Parkway, a highway that connects James City and York counties. Thomas, a recently discharged Navy lieutenant, and Dowski, a student at the College of William & Mary, had last been seen alive the evening of Oct. 9 in a campus computer lab, according to reporting by The Daily Press.

Roughly six months after David and Robin were found murdered, 20-year-old Richard “Keith” Call’s father found his son’s car abandoned at the York River overlook off Colonial Parkway the morning of April 10, 1988. According to the FBI, Call had been on a first date with 18-year-old Cassandra Hailey at a Christopher Newport University party in Newport News. As with Robin, clothes belonging to Call and Hailey were found inside Keith’s car, though neither victim has ever been located.

About a year and a half later, on Oct. 19, 1989, hunters found the bodies of 18-year-old Annamaria Phelps and 21-year-old Daniel Lauer on a logging road less than a mile from an Interstate 64 rest stop in New Kent County. According to reporting by The Farmville Herald, Annamaria and Lauer had left Amelia County on Sept. 4 bound for Virginia Beach, where she was set to marry Lauer’s brother, Clinton, on Sept. 25. They were last seen at the westbound rest stop around 1 p.m. on Sept. 5 of that year, though they should have been heading east. Later that day, the car was found parked at an on-ramp by the rest stop with no one inside. Much like David’s truck, the vehicle’s key had been left in the ignition and Daniel’s clothes and Annamaria’s purse had been left inside.

“At this time there is no physical nor forensic evidence to connect the Isle of Wight or the city of Hampton homicides to the the two in York County on the Colonial Parkway or the one in New Kent County,” Geller said.