The Edwards Virginia Smokehouse

Published 2:46 pm Wednesday, March 30, 2022

A Century of Ham on the James

First in a series on the history of Virginia ham

Story by Phyllis Speidell

Photos by John H. Sheally II

As anyone who has spent more than a few days in western Tidewater can tell you, country ham is not only a highlight of local cuisine, but also an integral part of the community’s history. To put it simply – country ham has put the area on the map. The Edwards family and their hams, in Surry for close to a century, epitomizes that connection.

The next time you bite into a tender biscuit stacked with paper thin slices of Virginia country ham, savor the distinctly salty tang and think about the Native Americans whose methods of curing meat led to our modern-day culinary treat.

Long before Capt. John Smith and the Jamestown colonists arrived just across the river from Surry, the local tribes had mastered curing fish and venison with salt and smoke. When the settlers introduced hogs to the area, they grazed them on an island a few miles downriver from Jamestown. The island is still known today as Hog Island.

The settlers, learning from the Indigenous tribes, turned away from the traditional English sun-drying process of curing meat and adopted and refined local curing techniques. They rubbed the pork with salt extracted from sea water, fueled their smokehouses with oak and hickory and allowed the smoked meat to rest for a time. The salt preserved the meat while the aromatic smoke added a distinct flavor to the pork. The struggling settlers survived on the smoked meat and exported hams to Europe.

“There are records in Surry courthouse of hams being shipped back to England and Europe in the 1600s from Surry County,” said Sam Edwards III, president, CEO and third-generation Cure Master of S. Wallace Edwards and Sons, also known as Edwards Virginia Smokehouse – or simply Edwards Ham Co.

The local curing process followed a seasonal calendar. Early winter was the time to slaughter hogs. The colder temperatures curtailed spoilage in the salt-packed hams. Once rinsed, the hams hung to dry, smoke and cure into the warmer weather.

The ham-curing tradition became part of the local culture with farmers adding their own touches to the process over the years.

S. Wallace Edwards, the founder of S. Wallace Edwards and Sons, grew up on Jones Creek, near Smithfield, and learned how his widowed mother cured hams. He married Oneita Jester, daughter of Capt. A.F. Jester, the man who launched the original Jamestown-Scotland Ferry. When Edwards joined his father-in-law as a deckhand, pilot and then captain on the ferry, he brought along ham sandwiches to sell to the passengers.

The sandwiches were so popular that Edwards, buoyed by his success, opened a hog-slaughtering and processing plant, curing his signature brand Wigwam hams in teepee shaped smokehouses behind the family home in Surry. Some of the smokehouses remain standing today just off the intersection of state Route 10 and state Route 31.

Another link between the Edwards family and local history – the restored deck house of the original Capt. John Smith ferry – sits on display on the grounds of the Surry County Historical Society. In 1925 Jester used that ferry, the first motorized automobile ferry to cross the James River, to open the Jamestown-Scotland Ferry line. The Edwards family, proud of Edwards Sr’s career as a ferry captain, were active in the deckhouse restoration efforts.

Edwards Sr. also drove his own delivery van across southeastern Virginia to deliver his hams and sausages to a growing list of customers from country markets to fine hotels.

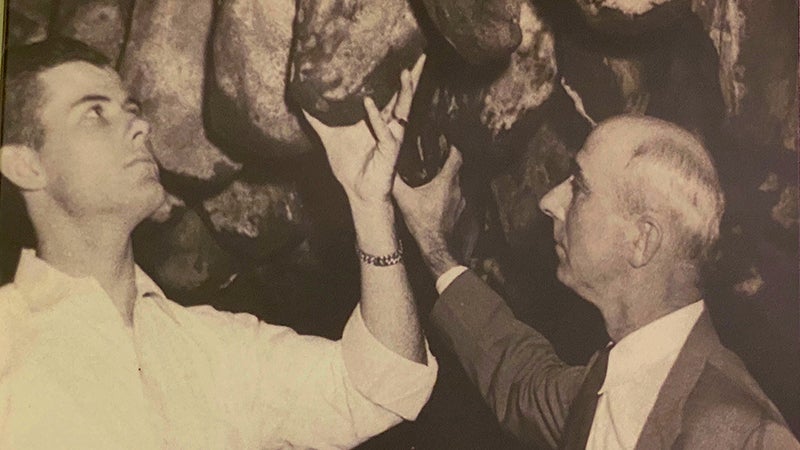

He and his son, S. Wallace Edwards Jr., nurtured the company, employed 120 workers and expanded with lard and cracklin’ skins production as well as hams and sausages. The family crafted their own curing methods, tweaking the air flow, temperature, timing and pork selection from humanely slaughtered hogs.

Edwards Jr. recalled standing on a street corner in Williamsburg in 1957, to watch the parade that escorted England’s Queen Elizabeth II to the Williamsburg Inn, where she dined on Wigwam ham. When the Queen returned 50 years later, Edwards was there on the same corner and, once again, Her Majesty enjoyed an Edwards ham.

Edwards Jr. eventually took over the business from his father and added his own innovations, including temperature controlled curing rooms. He also brought his son, Sam Edwards III, into the business. The younger Edwards continued to innovate and returned to his grandfather’s belief that their supply hogs should feed on Virginia peanuts to achieve their distinctive flavor.

Even with the passing of Edwards Sr., the company founder, S. Wallace Edwards Jr. and his daughter, Amy Edwards Hart, the company vice president, the company prospered with Sam Edwards III and his son, Sam Edwards IV, at the helm.

The Edwards family continued to innovate and explore new products, including the popular Surryano ham, a ham akin to a Spanish dry-cured ham and or a prosciutto.

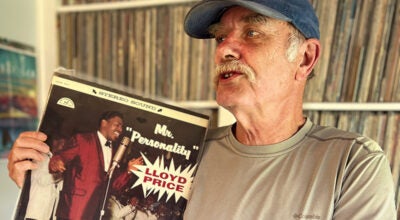

Sam Edwards III took Edwards hams on a “Cure Tour,” conferring with well-regarded chefs and food writers.

“We were developing a tasting wheel, similar to a cheese or wine tasting wheel, where taste and smell are viewed as two interconnected senses,” he said. “To be pleasurable any food has to have the right aroma to make you want to eat it and savor its inner flavors.”

With such innovative energy, the story of the Edwards Virginia Smokehouse might have continued happily and profitably but for a January 2016 fire that devastated the company’s Surry facility.

At 12:15 pm that day, Sam Edwards III smelled smoke, not unusual at a ham plant, but this smoke had a more acrid smell. He discovered a small fire in the electrical room and was grateful that most of the employees were at lunch.

“I pulled all the breakers I could,” he said. “But then I realized that only Virginia Power could cut off the power from the overhead power lines.”

The fire burned for five days until a foam truck finally subdued the last of it. Then, Edwards said, the vultures, coyotes and dogs went after the wreckage while the insurance adjusters took three months to complete their investigations.

Edwards said he initially saw the fire as a bump, albeit a big bump, in the road.

“I thought perhaps there would be room for improvements as we rebuilt, “he said.

“It took year-and-a-half finally get an accurate cost estimate to rebuild and, while we got what we were covered for, it was only a quarter of what we needed,” he added, “The insurance was based on outdated construction costs and the settlement would not come close to what we needed to rebuild, let alone build back better. Out of 50 employees we were able to keep only 19.”

A court battle over the insurance claim dragged on and remained unsettled in August 2021, when Edwards announced the sale of Edwards Virginia Smokehouse trademark and recipes to Burgers’ Smokehouse of Missouri.

While the company was fire-disabled, Edwards had outsourced production to half a dozen manufacturers, including Burgers’ Smokehouse, another family-run company and among the first to call offering to help. His parents had been close friends with the Burgers and that eased his decision – somewhat.

A temporary building on the former Edwards site now houses the new Edwards business – Oakvance Holdings Inc. – named after the Isle of Wight farm, The Oaks, where his grandfather grew up.

Sam Edwards estimates he has enough Surryano hams to last through 2022. Since the fire, Burgers has been making Edwards hams, both the country and city ham products, according to Edwards. Under Burgers’ coordination, smoked and fresh sausages are still made from the original Edwards recipe.

That’s good news for fans of Edwards products – including Sam Edwards. A confirmed ham lover, he keeps a home freezer full of ham, bacon and sausage to enjoy – with a side of history seasoned with memories.